Who is looking?

Brais Romero Suárez

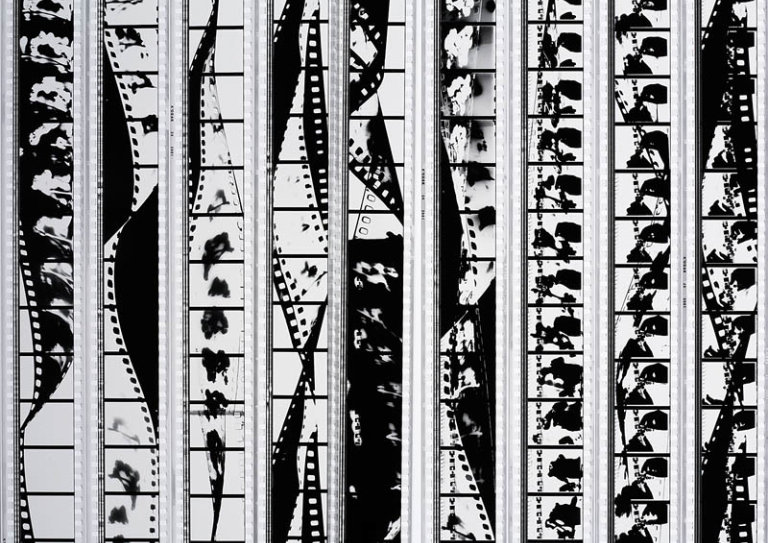

“Two planes interspersed by different images provoke different emotions”. Kuleshov At the beginning of the last century, Kuleshov studied this psychological effect, in which our mind filled in the spaces created by the montage with different meanings. Since Tscherkassky wanted to develop these studies, he revolutionizes the cinema by increasing the film projection speed in order to build an existing continuity only in the cinema. This is the Tscherkassky effect: the movement does not exist in the cinema (the film), but in the celluloid (the film projection).

The cinema is not just an art focused on capturing reality or reinterpreting it; the cinema is the answer to the human race’s passion to watch without being seen. It is the answer to an innate voyeurism that finds in it the way to externalize that drive. An allure that enslaves our eyes in front of the screen in the dark room, constantly bombarded by realities that only exist owing to the nature of the projection.

Tscherkassky is a craftsman of film and gaze subversion. His artisanal work with celluloid becomes films machine-gunned by images. He is a filmmaker who works with our desire to watch and takes advantage of our cinematic voyeurism.

From films like Holiday Film, where a woman walks naked through the woods over and over again like the dream of what was/is, to others like Manufracture, where movement is contrasted from a race car to a car park. Austrian films never offer us what we want. Expectations cultivated by traditional visual education provoke frustration with films that play with our subconscious and our predetermined ideas. Tscherkassky knows this, and that is why his films play around to reverse the traditional scheme that goes from the screen to the viewer: here, the film also looks at the viewer.

In Coming Attractions, the filmmaker is committed to stripping down our scopic drive by creating a series of film sequences where the film plays out to let itself be watched and watch. As in a sort of preliminary ritual, the film excites the viewer while pointing out the cause of it, causing the fact of being discovered to further sublimate the stimulation. The film also looks at itself, as we can see in the series of faces that cross looks that are possible in the montage, while we wait for our turn to be discovered again by the film. Like Tantalus in Hades, Tscherkassky places us between water and fruit, making it impossible for us to access both in a process in which frustration becomes agitation.

But, who is looking at whom? Who is the first to look? Happy-End involves recovering a family home archive. An adult couple is drinking and celebrating something we do not know about, while someone unknown films the scene. In Tabula Rasa, a woman undresses in front of the camera doing a striptease that never ends, the excitation is such that the film itself is infected and comes to life. In The Exquisite Corpus, a couple adrift on a boat find an island where a group of people await their arrival. But who is looking? A question that seems to be repeated throughout Austrian cinema that can only have multiple answers. Austrian cinema is the celebration of gazing, the analysis of it, the realisation that films are not just for viewing, but are experiences in which each viewer changes our perception and in which the author is not hiding behind his work, but rather he is located within it.

In Instructions For A Light & Sound Machine, we witness Tuco’s descent into hell, the character played by Eli Wallach from the classic film directed by Sergio Leone. The cowboy returns to the scenes in which the epic film took place to be studied under the watchful eye of Tscherkassky, who shoots violent bursts of images from within the film. Filmmaker and protagonist share a non-existent reality, in which Tuco struggles to recognise the desert converted into Hades, in which the cinematographic form is a tool with which the director not only reflects on the experience of the re-viewing, but with which he also modifies history, an idea that he explores in other works as well such as Shot-Countershot and Dream Work. The goal is not an exercise in nostalgia, but rather a radical transformation, in which there are hardly any signs of the originality of the images, and in which they are transformed into shadows of dark worlds. Dreamlike nightmares in which the images only exist in the projection, in which the mixed realities do not even share the same frame, but the very nature of the projection creates a new dimension in which the impossible becomes reality.

Tscherkassky’s films travel at high-speed. When the room becomes the darkened room, we enter into a dimension that Tuco inhabited, a dimension in which we will be watched and in which we will be able to watch, but in which our decisions are subject to films that move fast, like a train. Like Lumière’s train that arrives at the station in The Arrival, in which vehicle arrives at the station at the same time that the image reaches the frame; the train stops; but the cinema continues.

Read more

View less